The more time spent with these primary sources, the information subtly pops out at you.

Case in point: there is some room for discussion regarding the interpretation of cadences. We looked at them several times before (here, here, here, here, and here). From our perspective here at the Club, they represent extremely fluid and flexible embellishments that can be interpreted by the performer in ways allowing for a large range of interpretive expression: from quick, to tripping, to elongated and held.

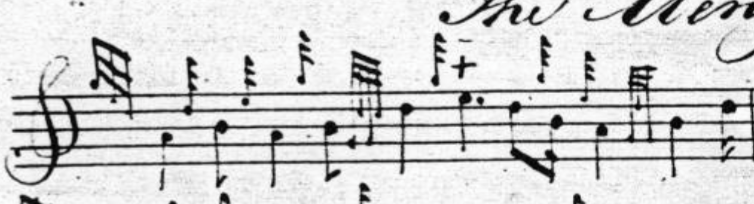

Of course, others have long argued that the way the cadence is performed today also has a very long history. This is clearly true, as we can see from numerous sources: certainly Angus MacKay very much approved of the held-E, standardizing it in his scores as a the dominant interpretive expression for a cadence. Check out these crahinin examples:

But we also see held cadences in Peter Reid:

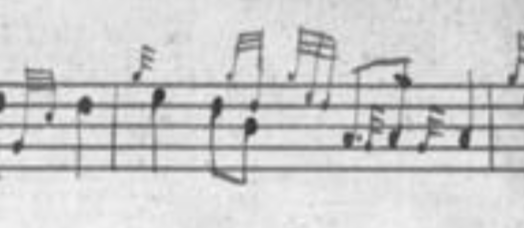

and even the anonymous transcriber of the Hannay-MacAuslan collection:

The question is: how frequently was this the case? If all we can was Angus MacKay’s writing, one would be inclined to assume this was very much the dominant interpretive form.

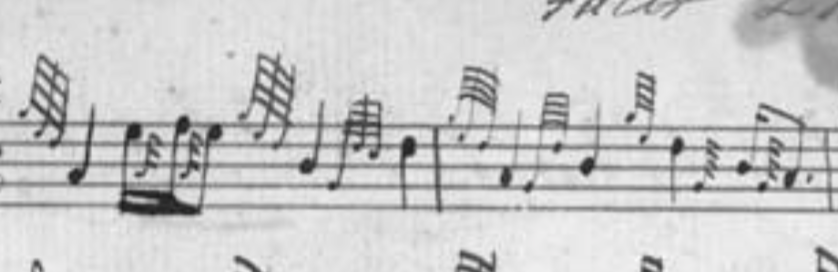

But turning to other scores, it is not so clear. Donald MacDonald likes his cadence runs. His tunes are full of them:

Hannay-MacAuslan and Peter Reid do as well.

But it is unclear whether their notation was literal when it indicates even tempo runs, or whether there was already an idiomatic presumption regarding it’s “actual” performative style.

In the absence of evidence one way or the other, no one perspective could definitively state their case, but neither could they be disproven.

Until now:

This is from Donald MacDonald’s manuscript. Note the fermata under the middle E of the second cadence.

It appears that this mark is original to the manuscript (not a later emendation). It therefore also appears that the transcriber was fully capable of and willing to capture this particular style of expression when he desired to do so - as evidence here.

It is also therefore possible to conclude: in the absence of a fermata (or indication in the staff itself), the E was not intended to be held.

There was no assumption of an “idiomatic” interpretation of the run - if the E were meant to be held, it would have been indicated as such.

And it was.

Clearly.

Some additional thoughts for pondering:

- This confirms the validity of the approach made here at the Alt Pibroch Club: that these manuscripts be taken as empirical evidence of specific stylistic choices of performers as captured by the transcribers.

- These transcribers were consummate musicians and musical theorists fully capable of retaining the quality of the performance they knew and heard. There is no empirical reason to doubt their scores.

- The insistence that notation cannot capture the living expression of musical performance may be true, but that only means it is up to the performer to provide the interpretation using all the tools at her disposal (rubato, expression).

- If there is any question about the accuracy of a score, that may be only due to the canonization and interpretive standardization processes of the last century, in particular. The plethora of interpretive options captured in the original scores themselves suggest remarkable differences, and the question of their accuracy only comes from our own desire to make them conform to our standards.

It appears that if Donald MacDonald wanted to cadence run to be a held-E cadence, he would have done (and in fact did) so.

When is a cadence not a cadence?

1) The example of “held cadences” from Peter Reid’s MS in ‘The Menzies Salute’ shows a long E between two D’s. But is this a cadence? The same E appears in the siubhal and subsequent variations, where it is clearly a ‘theme’ note, or integral part of the melody.

2) The Hannay - MacAuslan MS example (from ‘End of the Great Bridge’) purports to show an E in the urlar which is a cadence - but in the next variation, this E becomes a high A, preceded by a crunluath (!) which means it is not a cadence but a part of the melody.

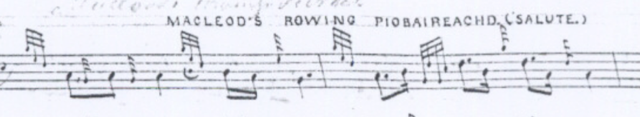

3) Donald MacDonald’s version of ‘MacLeod’s Rowing Tune (Salute)’ shows a fermata under the E introducing the cadence onto B A G. But it should be remembered that some played a long B in this sequence (eg John Smith’s MS), so Donald’s fermata may be an attempt to avoid ambiguity here.

John Smith’s cadence indicates the E as a semi-quaver, between two demi-semi-quavers; rather shorter than DMcD’s

If one tries to row to this tune, it is necessary to stress the first note in each motif, thus: A a A, B a G.

This is what JS does; his initial motif has a short introductory E and a long low A, rather than the shorter one implied by a ‘birl’. Donald MacDonald also has a long low A beginning the first motif.

So his stressed E with the fermata may be thought of as almost a theme note rather than a cadence, even though it does not appear in later variations.

The same effect could explain the long E which is sometimes played in the first motif: a need to stress the initial note for the purpose of an emphatic rowing rhythm.

You make some interesting points, Ronald, and spotted my mistakes quite well.

So let me begin to make amends by pointing out this interesting held-E cadence in “McIntosh’s Lament” as per our friend Peter Reid (PS 200). That E exists nowhere else in the rest of the tune, and yet is a really big E, isn’t it?

As for Hannay-MacAuslan: you are correct, the E has been replaced with a thumb A, but isn’t it interesting how it is the D that is the theme note throughout the rest of the variations? This suggests there is something very ambiguous about this E to my mind. That said, the anonymous transcriber was not prone to encountering many held-E cadences, and I find that particularly instructive when it comes to The End of the Great Bridge, since it seems an immutable fact that the first cadence of each phrase beginning with low G is more thematic than the original G theme note any more. I’d prefer to hear it as written by her, truth be told.

As for your ideas on Donald MacDonald’s version of MacLeod’s Rowing Tune, I find much of what you say quite reasonable. I simply find it fascinating that here we have direct evidence of held-E (for whatever reason), as indicated by a fermata. Which suggests that he was perfectly capable of indicating a held E when he saw fit to. And it is interesting how he did NOT see fit to do so, when compared with the MacKays proclivity to do nothing but give that E prominence every chance they could, whether by putting it in the staff as a thematic note, or by giving it one less flag when as a grace-noted movement.