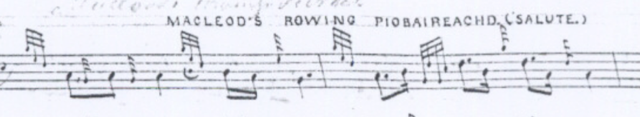

In 1870, Alexander Carmichael recorded a folktale about two of the most highly venerated saints in Highland culture, Moluag and Calum Cille (Columba). In a race to the island of Lismore, Moluag cut off his little finger and threw it ashore in order to be the first to touch the island. Could this be what Port na Lùdaig - The Little Finger Tune (PS 240) is about? As the musical use of the little finger in this pibroch is unremarkable, the legend offers a better explanation for the title.

I came across this folktale on the Carmichael Watson Project blog:

Moluag (530–592) was an Irish missionary, educated and trained in Bangor, who came to Scotland and is believed to have founded over 100 communities during his lifetime, the most significant being at Lismore, Rosemarkie and Mortlach. His name has been recorded in Irish as Lugdach and Lughaidh, and in Latin as Lugidus, Lugādius and Luanas. His name also often appears with the diminutive of endearment – Moluoc. A popular belief is that his name is derived from mo ludag – my little finger – but this surely is based on the circumstances by which he claimed Lismore (noted below).

He was a contemporary of Columcill and the following account of how Moluag came to settle on Lismore provides an insight into their relationship:

After looking around him in Argyll, S. Moluag resolved to settle in Lismore – the green island in Loch Linnhe. S. Columba heard of his determination and resolved to forestall him. According to the Gaelic verses (Carmichael), which have been passed down from lip to lip for centuries, as S. Moluag approached Lismore he beheld a boat containing S. Columba making for the shore at highest speed. S. Columba’s craft was the faster, and when S. Moluag saw that he was going to lose, he seized an axe, cut off his little finger, threw it on the beach, and cried out “My flesh and blood have first possession of the island, and I bless it in the name of the Lord.”

This version was told by Rev. Archibald B. Scott in 1911 (see below, p. 313). Regarding the importance of Lismore, Carmichael notes (Carmina Gadelica, iii, p. 4):

What is now the parish church of Lismore was in pre-Presbyterian times the chancel of the Cathedral Church of the See of Argyll and the Isles, and was called Eaglais Mhór Mo-Luag, the Great Church of Mo-Luag.

Carmichael was born in Lismore and collected this story from a kinsman on one of his trips home. This is what he recorded in his notebook in 1870 (CW106/2, folio 5r), the earliest source that I have found:

Friday 2 Sep. 1870 from Oban to Lismore.

Mr Duncan Carmichael in the boat who told me Calumcille Maoluag and Ordhean were brothers

M[aoluag] & C[alum Cille] were making for Lismore & each try[ing] who sh[ou]ld be ashore first M[aoluag] put his finger on the tot [tobhta – rower’s bench] & cut it off and when near shore threw it ashore say[ing] Tha m fhuil us m fheoil eir tir agus s lioms an t eilean [Tha m’ fhuil is m’ fheòil air tìr agus ’s leams’ an t-eilean – My blood and flesh have landed and the island is mine!] & then Maol[uag] got Lismore & Cal[um Cille] went to Iona (Ithona).

This was published on the Carmichael Watson Project blog in 2011 and I am grateful to Ronald Black and Allan MacDonald for helping me with the editorial explanations in square brackets. Ronald explained the variant spellings of Columba’s name as follows:

The correct Scottish form in the nominative case is Calum Cille and that is what I always use. The correct Irish form in the nominative case is Colm Cille. Other forms that you find are oblique cases, garblings, slight anglicisations etc. And you will often find what looks suspiciously like the “Irish” form in Scotland, because of course it is also the “Classical Gaelic” form.

Two elaborated versions of the story are found in the following publications:

Carmichael, Alexander, ‘The Barons of Bachuill’, The Celtic Review, v (1909), pp. 356–75.

Scott, Rev. Archibald B., ‘St Moluag and his Work’, Transactions of the Gaelic Society of Inverness, xxvii (paper read 9 March 1911, published 1915), pp. 310–323.

Rev. Scott assembles substantial evidence that the rivalry between Moluag and Callum Cille was not merely fictional. Moluag seems to have done more to Christianise Pictland than Calum Cille and was equally active in the Hebrides, founding churches in Tiree, Mull, Trotternish, Raasay, Pabbay, Lewis and Morvern. From the perspective of Gaelic-speaking pipers, Moluag was probably Calum Cille’s equal. It certainly seems plausible that this vivid tale should give rise to a pibroch - especially given the legend attached to The Red Hand in the MacDonalds’ Arms (PS 252):

The Clan Donald hero of the story sprang to the prow of his galley, and with a stroke of his dirk cut off his hand, and cast it upon the shore, thus obtaining the lands for himself and his descendants. To this day the crest of the MacDonalds is the bleeding hand. (History of the Clan Donald, 1920, pp 22–23)