Yesterday I stumbled across this in an 1812 book of drum beatings:

Singlings of Troop or Assembly (p. 6)

Doublings of the Troop (p. 7)

Singlings and Doublings of the Tattoo (p. 8)

Doublings of Troop (p. 31)

The Troop and Tattoo are military signals, notifying soldiers what to do. The evidence for pibrochs being used as military calls (Reveille, Troop, Retreat, Tattoo and General) is found here.

A New, Useful and Complete System of Drum Beating – Including the Reveille, Troop, Retreat, Officer’s Calls, Signals, Salutes and the whole of the Camp Duty as practiced at Head Quarters, Washington City; intended particularly for the United States Army and Navy by Charles Stewart Ashworth, Leader of the Marine Band of music, Washington City. To which are added Tunes for the Fife adapted to the Drum. Boston, Published for the Author 1812 by G. Graupner

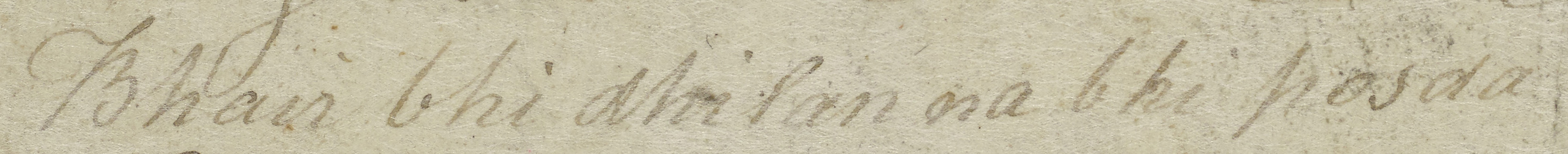

A couple of months ago, I noticed another thing that may throw light on where the pibroch terms “Single” and “Double” come from. The choreographic terms simple and double are abbreviated to S and D in notations of court dances from around 1500. These abbreviations and the alternation of measures (choreographic units) of different length immediately bring to mind Colin Campbell’s Instrumental Book:

Basse danse. The principal court dance during the late Middle Ages and Renaissance. It reached a height of cultivation during the 15th century and disappeared after the middle of the 16th century. The musical practice that grew up around it served as a proving ground for many early instrumental techniques such as improvisations over a ground, variations and the forming of suite-like combinations.

… the dance was performed by couples and employed only five different step-units: R (révérence); b (branle); s (simple, usually found in pairs); d (double) and r (reprise or des marche). These five steps were combined into codified patterns called mesures. Several mesures made up a complete dance, some dances being of six mesures (a total of 62 step-units, as in Le doulz espoir). A typical choreographical structure involved alternation of one mesure with another of different length.

Daniel Heartz and Patricia Rader, ‘Basse danse’. Grove Music Online. Oxford University Press (accessed November 2015)