Here we air our dirty laundry: academic pursuits are a messy business. Hypotheses, testing, failure, new hypotheses are the name of the game. All too often, it is the final hypothesis and its proof that is presented to the public, giving the impression of both clarity of thought and self-evidence of conclusion.

Human minds are never so tidy.

In contrast, our effort at laying out our proposals regarding genre classification and their performance implications is meant to stimulate discussion and prevent calcification of the boundaries by laying out the processes by which we wrestle with this issue.

In today’s post, we argue about over the best means by which genres may be identified, by reference to a number of possible approaches. David tends to favor inductive empirical musicology; Barnaby, while not ruling that out, wishes to introduce the insights of musical psychology.

We have not yet settled our differences (such as they may be), nor have agreed upon a way to proceed beyond the initial work presented (and still extent) on AltPibroch: Genres.

This is something we will continue to work out, here.

JDH - In our discussion of genres, and the hypotheses you proposed in a post, and in my response to that post: according to both of our hypotheses, the Birth of Rory Mor MacLeod (PS 131) ought to be a lament.

BB - No. That’s only when you take it out of context. You have to have more than one of these criteria; these are potential, non exclusive criteria. Yes, Rory Mor is a higher tessitura, but because it lacks reinforcement from any of the criteria…

JDH - That’s not true. I’ve taken another look at it: it has lots of double-beats. There are at least 4 double-beats.

Let me tell you why I want to raise this: if my definitions of the genre are such that a celebratory tune (by title) fits the criteria for lament, I need to redefine the criteria.

BB - Yes, you do. You have got to leave behind any simplistic definition, and put together a much richer pool of qualities that might add up to the feeling of a lament. You’ve got to bear in mind that the feeling of a lament accrued culturally by the tunes one knows.

For example: the idea that major is “happy”, or the idea the E-flat major is associated with victory - these things are the result of knowledge of particular pieces of music. And in any musical culture and musical tradition we grow up encountering pieces of music and our particular associations we have with those pieces of music. It’s not scientific. We are human beings, we are not computers who process auditory data in the kind of way we might initially think about it, from the point of view that we are superior and scientific.

We’ve got to realize that the scientific approach is terribly crude.

JDH - I would agree, and am sympathetic to your argument. However, to my mind, one of things that needs to take place is, rather than a fluffy intuitiveness which has resulted in the making of all pibroch pieces into one big bland genre, the only way can begin to differentiate genre from genre is by getting more critical and providing the kind of apparatus that allows other people to pick it up and replicate the results of our work.

Otherwise, the reliance upon intuition (aka “cultural experience”) is going to be something that will misrepresent the results, since we are talking about immersion in historical developments that have eventually brought to the place where we currently are: All cats are gray!

What I am trying to introduce is a bit more rigor, to address the definition of lament based upon tunes with the title “lament”. We play them like laments because “that’s the way we play these tunes.” We have a situation where definitions are all encompassing and self-referential. This situation needs to be addressed.

Now, when I view 73 titled laments (pre-1840), their musical structure is all over the place. That tells me there is a lot of history we need to dig through. Which means we need to identify key musical criteria that help us pick out certain forms of laments from other forms of laments, and not try to create definitions that lump them all together.

BB - I think we agree. I don’t think we have any fundamental disagreement on this point.

JDH - So what about my three criteria fail? What is missing from them, such that Birth of Rory Mor Macleod is included in “lament”?

Even “The Pretty Dirk” meets the criteria.

BB - You just need to be much more complex. I feel the thing to focus on is grief, the sound of grief, particularly that of people crying. And grief vocalization tends to be higher pitched.

Now, consider laughing: there’s not a big difference between the sound of joy (crying with laughter) and the sound of grief. That similarity must be born in mind. That might partly explain why the Salute on the Birth of Rory Mor might have some of the same qualities we’d expect to find in a lament.

What marks it as something joyful rather than something tragic? I would suggest that we have a much more lively melodic line: it’s bouncy. It doesn’t sit. As say the Lament for the Laird of Arnabol does: you’re just sitting still on that high G.

Whereas in Birth of Rory Mor, you have much more energetic movement bottom to top, a wider ambitus with more motion, and obviously its contingent upon interpretation and the speed you play it at: you can make something sound like a lament just by slowing it down.

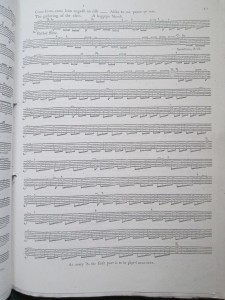

JDH - Which is interesting because in Donald MacDonald’s book, this pibroch is marked “very slow”.

BB - Ooo. Isn’t that interesting?

JDH - But then, when the variations hit, he states “somewhat lively”. So, this is going to be an interesting struggle. Because, to my Western classical music mindset, you can take any tune, transform it to a minor key and play it slowly, and you’ve got a lament.

If we can’t really rely upon speed (since today we play everything slowly, and only a few of the early books and manuscripts have any tempo markings), what about key? Birth of Rory Mor is written in A Major, for example.

BB - My alarm bells ring loudly when you use terms like “major” and “minor”.

JDH - Oh come on. We have a diachronic scale. We know tunes composed in major and minor keys on the instrument.

BB - Yes, but that’s an anachronistic viewpoint to the mind of somebody composing a tune in the 17th century: you’ve got a very different set of musical practices against which you conceive these different sets. Major and minor tonality crystalizes in the 18th century, in a later Baroque.

JDH - Wait. We can go clear back to the Greeks and we have modalities back then.

BB - You mentioned a two-fold distinction: major, minor. That two-fold distinction had back in the 17th century had not yet emerged.

JDH - Alright. I am using modern shorthand. You’re right.

My problem is, I’m not sure which modal was being used.

BB - Again, I don’t think that’s really helpful. We really need to discard that baggage.

JDH - Absolutely not! We have beautiful stuff here that play within modalities. And we have musicians here who understood modalities. And maybe modalities are the key to this stuff. Maybe there are modalities that are favored in certain styles of laments vs others.

Even Joseph MacDonald sought to identify “modal” (he called them “keys”) chacteristics. It’s a natural part of a musicians experience to think of music in terms of modality, keys, etc.

So perhaps there is a kind of representative modality to “laments”.

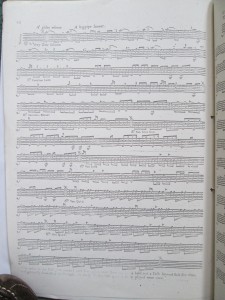

BB - I thought of that, when I started looking at this, I was looking (in my undergraduate dissertation in 1994) all the pitches at all the tunes in the Piobaireachd Society collection, I expected to find that laments would characterized by certain keys (for want of a better term), and I didn’t. The only thing I could find were characterized by higher tessitura.

I tried to organize it by A-pentatonic, G-pentatonic, D-pentatonic, and all the other different hexatonic possibilities, I laid them all out and the same number of laments were found in every single group.

What I found very, very clearly, in the less geometric urlar designs, you had a lot more laments. And in the higher tessitura tunes, you had a lot more laments.

JDH - And yet, I can count 25 laments that were neither particularly high-pitched, and many of them are geometric. So that can’t be categorical: there are plenty of low-pitched, woven ones.

BB - This is where you need to accept not all oak trees do not look alike.

JDH - I find that sloppy.

BB - But what do you do about a composer who is bloody-minded and wants to do something different?

JDH - The only way we can indicate that it is something different is by having something to compare it to.

BB - Okay, so we have a proportion, and this is deviation.

JDH - By 1/3, a third! That is a huge deviation.

BB - You’ve not looked at hierarchy. In the data I’ve provided, I don’t just identify pitches, but assign bold to certain pitches. Now, I think that’s the first step in being a bit more subtle in the analysis. You may have tunes where the low hand is dominant, but maybe have bold assigned to the upper tones.

JDH - And what are the criteria for determining this weight?

BB - It’s relative, and (as I acknowledge in the Map) is limited by the fact that it is impossible to be empirical at that stage, because of all the notations. So, I’ve discarded cadences. I then look to assign one of four levels to a pitch: 1) it’s absent, 2) prominent due to its level of scarcity, 3) normal, or 4) prominent by virtue of being more present.

I define three ways by which it may be more salient: one is when it is long (sustained - like two double beats); another is when looking across the whole ground, the duration compared with all the other pitches; but possibly more importantly, is it on a strong beat (at the start of syntactically significant units)?

I think the brain, when we hear a bit of music, is doing something more than counting pitches; there’s something a lot more sophisticated going on in our processing of the auditory data. And in order to come to conclusions that are valid, we need at least to try seriously to recreate in our model the kind of complexity experienced in our auditory processing. And music is not a simple thing.

I presented a series of hypotheses in an effort to pinpoint a basis for being more scientific about, and achieve a kind of complexity in our modeling in how we perceive pibroch. Because, ultimately, it is what’s going on in the brain. And the idea of something being a lament or not, is a human response.

JDH - What I am questioning is the fundamental assumptions behind these hypotheses. I want to get a clearer understanding of these hypotheses and how we can see them in the music before coming to conclusions about the validity of their formulation.

BB - Let’s get specific then. Let’s look at the 6 hypotheses. I think, unless we hone in on particularities, we will be working at cross purposes.

JDH - Hypothesis One: higher pitch.

That has to be quantified.

BB - Yes. Hypothesis One is about wailing, about high-pitched grief. We’re more likely to find this in laments.

I propose you would encode 312 variation doublings, potentially just the second half of those variation doublings (because doubling discards all sorts of unknowns). The variation doublings provide you a simpler way of statistically processing the (relative) durations (and presence) of thematic notes. In the composition of pibroch, the flexibility (tempo rubato) is reduced in the variation doublings compared with Urlar: by the time you get to the doubling, you have a distillation.

So, if you were inputting the data (we don’t already have it input), then it would be relatively simpler, quicker to encode second halves of variation doublings. It’s a labor-saving choice. The pitches in the doubling are all equally long, so you don’t have to weight them as you would have to do when you encode the ground.

Encoding the ground you have quavers, crotchets, minnens, and in canntaireachd you have no rhythms to refer to: to encode the ground requires a lot of interpretation to encode.

Using the variation doubling is a way of reducing a lot of experimental interpretation of the evidence during the encoding process. It would result in a data set that is more consistent, with less chance of introducing variables, and would allow you to compare like with like when dealing with different sources: You are dealing with a lot of different sources, and you can’t just scan the Campbell Canntaireachd and Angus MacKay. You wouldn’t be comparing like with like.

That’s a suggested methodological approach for Hypothesis One.

Now, that methodlogy doesn’t work with the other hypotheses. Each hypothesis requires a bespoke metholodoly.

Additionally, the statistical significance of each hypothesis is going to be different. However, in the make up of a lament, what I am suggesting is that you have different proportions of characteristics: you can make a pudding using different ingredients, but it’s still a pudding.

JDH - Yes, but what I am suggesting is that just because it is a pudding, doesn’t mean they all taste the same.

So, do we look for a combination of these hypotheses whose combination tells us definitively, “This is a lament!”, or does each hypothesis identify a specific kind of “lament”?

BB - I invite you to read the line right after the presentation of the hypotheses.

I predict that these six hypothetical characteristics of a pibroch lament carry different weight and are present in different proportions, with only a couple needing to be present for a pibroch to be perceived by a cultural insider as a lament.

JDH - Okay. How many?

BB - Well, it’s variable. I’ve suggested that you only need to have a couple. I think you do need to have more than one, but my hypothesis is you need some reinforcement of these ingredients. If you have all six, then you very clearly have a lament. If you have only two, the identity might be so clear. It’s always going to be difficult to know, because of the question of who is judging the perception of lament. The only real evidence we have about how people in the past thought is the word “lament” in the title.

JDH - I know, but that can only be the starting point.

BB - But it’s one of the ways we could compare with a modern response. But bear in mind, the modern response will be different: is it the response of somebody who knows pibroch? who’s had a traditional pibroch education? the response of somebody who knows the unpublished material? of a piper who comes at it from a band environment? listening to Spotify is aware of other lament traditions? Heavens, the way we respond to music is a cumulative result defined by our encounters.

JDH - I agree, but I want to table that. There are too many variables at that point.

BB - In that case, the only thing that you can measure with these hypotheses is the occurrence or nonoccurrence of “lament” in the title. That gives you a scientific measure.

Or, you could approach it this way: you are looking for these musical qualities (hypotheses), blind to whether there is lament in the title (50/50), and then analyze the tunes according to the hypotheses and see what results. It would have be equal measure “lament” and non “lament”. Having done that study, you can compare the results with the presence (or not) of “lament” in the title.

JDH - Yes. That is one way. And I could do that.

But consider this: Look what I did with “Life & Fury” (Gatherings). I looked at all the gatherings inductively - I identified a very defined pattern that popped up in a few of them, used that as the standard, then went outside of titled “gathering” genre to the full collection and found a few more.

Now, what was left out? Are they not “gatherings”? Possibly. Are they gatherings of a different sort? Possibly. More exploration is needed. But the key is: here is an identifiable set of tunes with extremely similar structure. As such, I can choose to use it as the touchstone against which to appreciate or differentiate other “gathering” tunes as variations from or within the genre.

BB - So, in order to run a statistical analysis, you would need to have the same number of tunes with “gathering” in the title, and tunes without “gathering” in the title. And then you would run your tests and see what came out.

JDH - Perhaps. Maybe statistical analysis is the way to do this, but I think any genre critic would be puzzled by the idea.

By the way, we still have “Marches” and “Salutes’ to consider….

BB - We need to eliminate “march” from the discussion. “March” is a word for “pibroch”. Salute is a “failte”, and it’s not just a piping genre, it’s genre of poetry and harp music, and a lot less defined.

JDH - It seems to slip into the “lament”, some of the salutes seem to have some of the criteria we are talking about here.

BB - Yes.

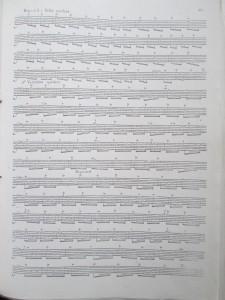

JDH - But going back to my initial foray into defining “laments” (with the three characteristics; I will have to take a look at your six and append accordingly): I found ten “laments” that had no woven structure and a prevalence of double-beats, but a low tessitura. I found seven “laments” that had a high tessitura and a lyrical structure, but no double-beats. Then there are three that had high tessitura and a prevalence of double-beats, but were woven (not lyrical). Those are interesting differences, but one could be generally comfortable with understanding them as “hybrids” of a “core”-style lament (for lack of better terms).

Nevertheless, what was left was an astonishing number that were called “laments”, but only had one of the three characteristics I identified.

BB - The ones that don’t fit I would put center stage and have a real good look at, because they are the ones that will help us get clearer in our definition.

What I’d like you to consider (I’d love to help devise something) is that part of our problem here is the decision to use headings where we have to divide things into discreet groups. Now blue and green in the rainbow, we might tidily divide them in a color chart and put all the blues on area and all the greens in another, but depending on a number of factors (including ambient light) there is an area of overlap.

What I find unsatisfactory in the way you’ve divided these tunes is the black-and-white of it, the sharp division between one group and another.

JDH - Oh, I know. And I know it’s going to be painful for you, but you know why I’m doing it: without a line, we don’t have definition, and without definition we don’t have terrain. Instead, we have a blob. And I’m trying to create a terrain where there is a big, fuzzy blob. Terrain shifts and change, but that what I want to do: bring details into focus by creating definitions that create malleable, but nevertheless definable boundaries that let us talk about, “How come this is called a lament, when all these other laments don’t sound like it?”

This is the kind of discussion we don’t have lot of, do we?

This process brings up stuff that let’s us ask such questions, which may lead us to exploring new ways in which we might play different kinds of laments differently.

BB - That’s where it gets fascinating, and unfortunately insoluble. At the end of my post, I put in two things that I didn’t make hypotheses because I don’t think you can answer them:

-

In the internal timing of double beats, were performers at an earlier period more likely to lengthen the second finger strike, and to increase the separation of the two strikes, in laments?

-

Were they more likely to play longer appoggiaturas (or ‘held streams’) in laments?

Now those are aspects of performance that lie below the radar, they’re not picked up in our source material. That’s why we can’t test them. But I think we need to consider them, have them in the back of our minds when running these tests, just in case we do run across any evidence in the source material.

These are ideas that are very relevant to the idea of lament. I feel the longer appoggiatura is something you do because you are feeling more emotional or you want to make a cry. It’s part of your toolkit as a musician: there’s more pathos generated there. I think that’s something biological, it’s not just confined to pibroch. And I think that the meaning of those appoggiatura, the emotion import are why we tend to play non-laments as laments.

I think it’s because laments give people great pleasure, in a completely physiological way.

So people in a “one-tune” scenario, where you are only given the opportunity to play one tune: it’s in your interest to play a lament, and to give non-laments that higher status by using something like held cadences (something lament-like), and derive greater satisfaction to the listener and yourself.

I think we must understand why we do what we do, rather than jump up and down and get angry, confrontational.

JDH - Well, I think discussions like this are going to be very useful and valuable to our readers and fellow performers. At the very least, it may get them thinking about things they simply haven’t had occasion to think about.

Wait until we get to the question of “salutes”!

Still more to come…