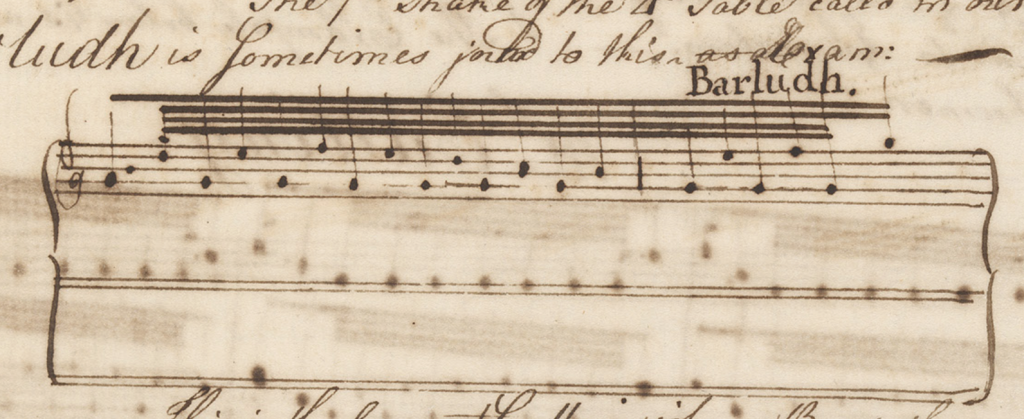

We assume that a barludh is this:

(Alan Bevan said that when he heard Barnaby Brown play this, it sounded like an earthquake!)

If you look carefully, however, the barludh is the movement appended to the end of the 18th Cutting to make this rather impressive flourish. (I assume this would make it the 19th Cutting, but it isn’t indicated as such.)

A Barludh alone is what we call a “G-throw” (embari in canntaireachd).

The term ‘barludh’ is also found in Clarsach music, as students of that art will confirm, and refers to a throw like the one on high G above.

An interesting observation is that it contains what has been referred to earlier as the ‘modern’ way of playing the tuludh and the crunludh, on low G and WITHOUT a redundant A.

Learning to play it means simply building on fingering already in use. It is an excellent way of warming up and keeping the fingers supple, once mastered.

Based upon this is it reasonable to speculate that:

‘Bar*’ (‘bari’ or ‘barluath’) represents s series of grace-notes based upon ‘low G’ or ‘low A’ or conceivably ‘B’ or ‘C’ or ‘D’? ie the example above is ‘low G - E - low G - F - low G’.

On the other hand ‘Dar*’ (‘Dari’) is a ‘trill’ ie ‘E- F - E - high G - E’ and ending on ‘F’ or ‘high G’.

I’ve been playing ‘bare bari’ ( in the last line of the urlar of ‘Slanfuive’) as two grips - low g, d, low g.

On the other hand, in the last two lines of the urlar of ‘Fhear Pioba Metic’, is the passage ‘Hadredarihin’, which seems to require a high g cutting followed by an f, both on E, before going up to high G.

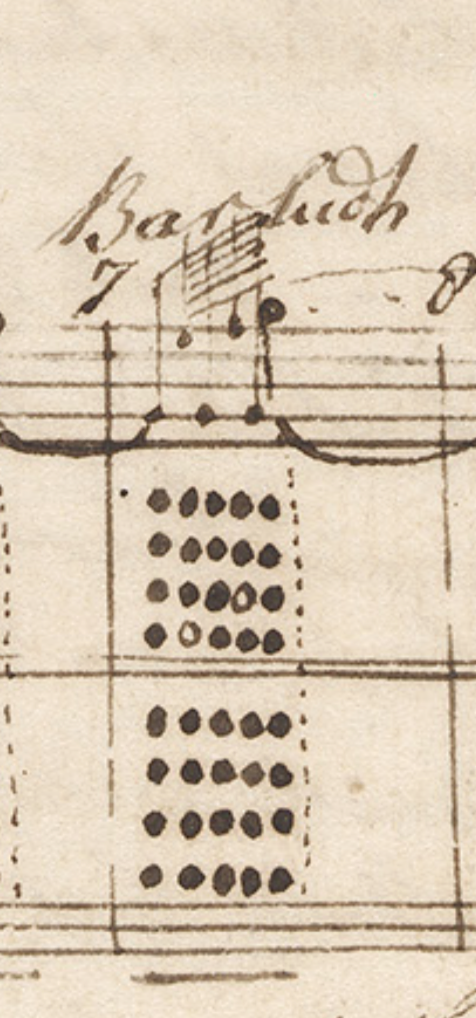

Here’s the Gaelic harp equivalents:

Barrluth

Barrluth beal an-airde

Barrluth fosgailte

This evidence seems to me to go in a different direction from the piping evidence - I would say barrluth was a kind of trill.

In modern Scottish Gaelic orthography, the spelling would be barrlùth, with two Rs and accent on U. The suffix “luath” makes no sense here, because that would make it a compound of two adjectives rather than an adjective and a noun: lùth means movement whereas luath means fast.

Bunting gives the translations Activity of fingers / Activity of finger ends / Activity of finger tops (p. 25). This makes no sense for the pipe movement and is unconvincing for the harp movement because they all involve the fingertips. Barr- is a common prefix with meanings in the range [top, highest, superior, pre-eminent, most refined], so a better translation for this technical term might be [high or supreme movement].

Having spent some time working on these issues, I have come to the conclusion we will never be certain unless new material is discovered (not impossible).

Can anyone account for the problem that the lemluath movement should be ‘ban-e’ rather than ‘bar-e’? Taorulath should be ‘ban-en’ rather than ‘darit’? Crunluath should be ‘ban-e-dre’ rather than ‘ban-dre’?

Are we all wasting our time over trivialities - are these differences THAT significant?

In 1999, I bought an Ardival ‘Rose’ harp, grew my fingernails and briefly toyed with the idea of becoming a harp player. That’s when I discovered and fell in love with the barrlùth fosgailte as documented from the harp tradition by Edward Bunting. I am grateful to Bill Taylor for achieving what was beyond me, investing a great deal of practise time over the last 12 months, developing his command of this finger movement. The CD with the end result goes to press later this week and will be released by Delphian in May 2016, but you can hear a preliminary result recorded a few weeks before we made the CD at http://www.altpibroch.com/learning/bill-taylor-ps135-on-harp/. The Barrlùth fosgailte starts at 8:40 and I certainly rank it as one of the most refined of the harp ornaments - a ‘supreme’ movement, rather than a (finger-) ‘tip’ movement.

In response to Allan’s concerns over the representations of finger movements in Campbell notation, I think these problems only arise if you think of canntaireachd as a notation system. The problems disappear when you treat Campbell’s text as a notation system - ‘Campbell’ notation. In my own writing and speaking, I now reserve the word canntaireachd for the art of vocabelising - not what you read or write, but what you do with your voice and hear with your ears. The writing is a complete irrelevance; vocabelising is about how you communicate finger movements using your lips, tongue and vocal chords to another person’s ears.

It really helps to COMPETELY disentangle these two things: Campbell notation and canntaireachd. They are different beasts, evolving in response to different environments, serving different purposes. If you can succeed in undoing a century of thinking and writing in which they are inextricably bound up together, then the problems you are wrestling with will, I believe, start to disappear. A tall order, I appreciate!

It looks to me like you are interested in a notation system. Campbell’s is far from perfect and in many ways is a job in progress. Rather than continuing his course, developing a notation, my interest is in understanding what his evidence tells us about the art of vocabelising when there was nothing on paper, i.e. before Joseph MacDonald and Colin Campbell.

An interesting thought following Barnaby’s admirable explanation of the difference between singing a tune (canntaireachd) and Campbell’s written notation arises from one of his tunes, CC V2 59, ‘Day yesterday and here yesterday’ (Queen Anne’s Lament).

The first line begins: ‘Hinde hindo hio endo cherede…’

The conundrum of this name can be solved if one looks at the Gaelic words corresponding to the English ones: ‘Diugh an de is seo an de’ (an de = yesterday, an diugh = today, an seo = here, is (agus) = and).

Someone has interpreted the first few vocables as Gaelic; what emerges is that Campbell’s notation, if pronounced aloud, sounds like the Gaelic words, which have then been translated into (nonsensical) English.

This seems to indicate that his notation system was not entirely divorced from the spoken or sung language, but was still somewhat oral in nature. The spoken rhythm of the gaelic also provides a hint as to the phrasing of the first few notes: ‘hin DE hin DO, HIO en DE’, or ‘HIN de hin DO…’